The Web3 We Weave

written by monadnomad

In one short year, fxhash has assured its place in the history of generative art. While other platforms have aped the traditional gallery model of curated artists and high prices, fxhash has set itself apart by embracing the open and democratic principles of web3. Lower mint prices, no barriers to entry, a passionate community in which collectors turn creators and vice versa – this is truly a platform for the people and the culture.

It’s tempting to attach too much significance to first things. The NFT art world is always hyping “genesis” collections. But it is remarkable that among the very first mints on fxhash – number 79 – appeared a work of such conceptual kinship with the platform that, one year on, it feels almost like an accidental manifesto or call to arms. That work is Andreas Rau’s Loom.

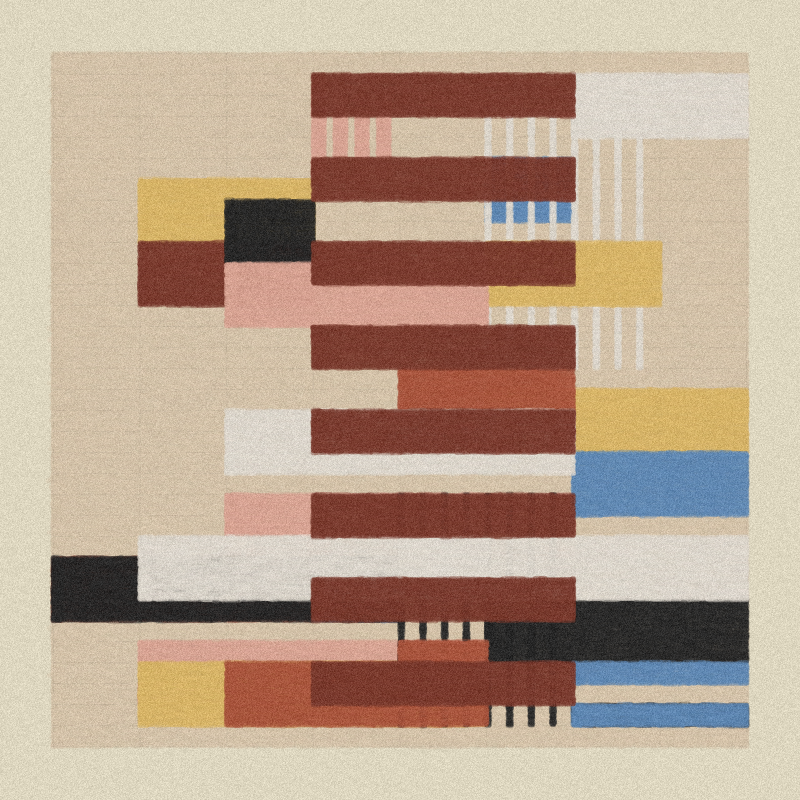

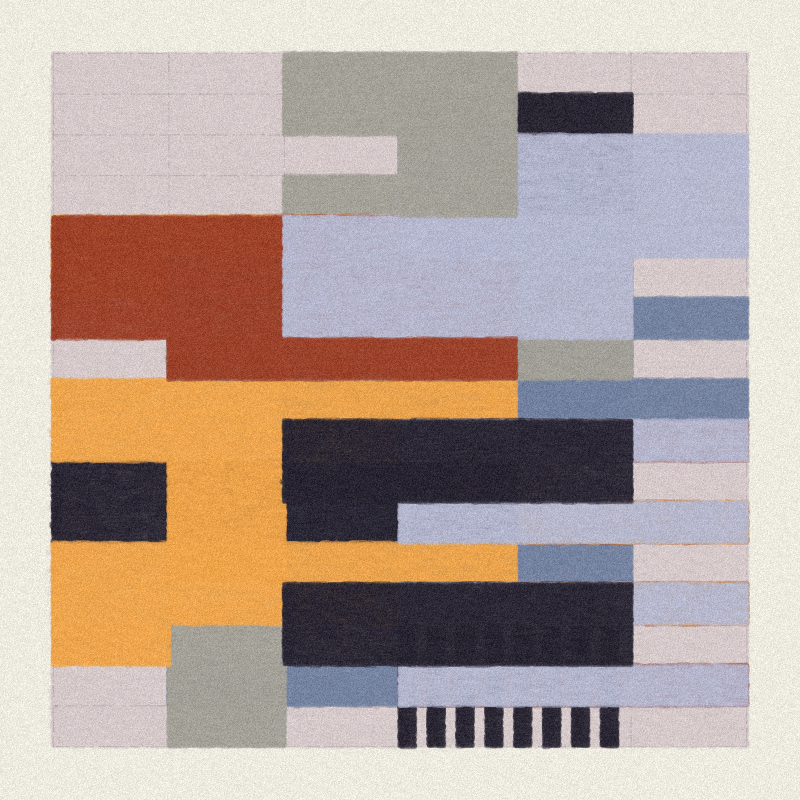

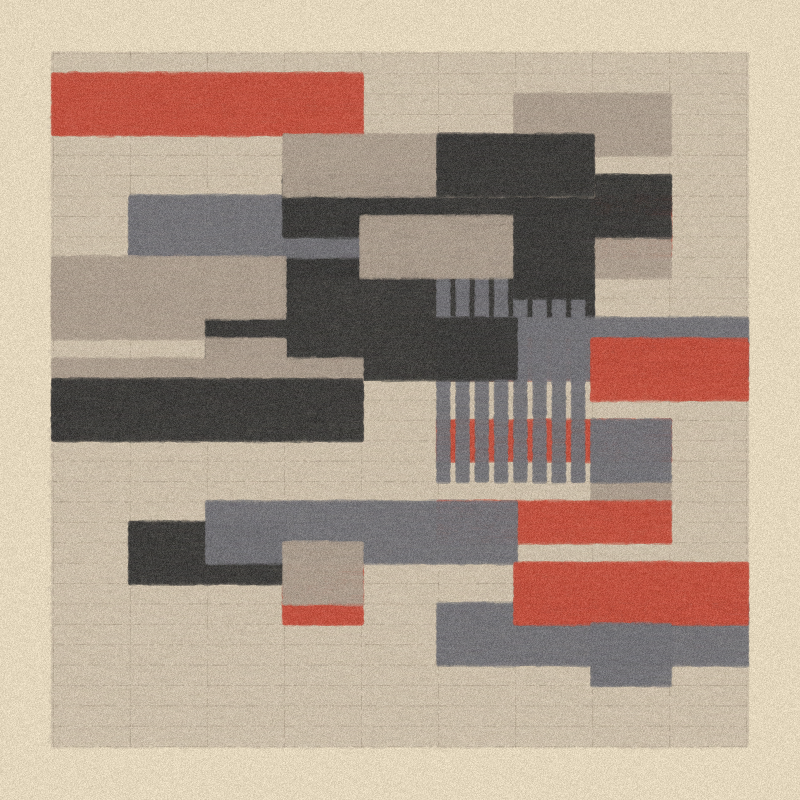

Loom is an elegant study in hard geometry, soft textures and exquisitely balanced palettes. Its debt to modernist textile design is acknowledged by the largely unsung female modernists for whom its palettes are named: Anni Albers, Gunta Stölzl, Sophie Taeuber Arp and Hilma af Klint (all worked with textiles except the latter, a proto-modernist pioneer of abstract painting. Only 7 “Hilma” iterations exist.)

project name project name project name

But there is more to Loom than that – and the title seems a good place to start. Note that Andreas Rau did not name it Tapestry or Rug. The title Loom – a device for interlacing thread into a fabric – asks us to think not just about the finished work, but the means of its making.

As fans of generative art, this is something we must all learn to do. A longform generative artwork finds expression in a finite number of outputs, each of which can be admired as a standalone piece. But it’s in exploring the variety of iterations that we come to appreciate something deeper and less tangible – the algorithm that lies behind the work. Some people even consider the algorithm to be the artwork, casting iterative shadows on the wall of the cave. It’s by contemplating the algorithm – this beautiful collaboration between human and machine – that the whole of a work emerges as greater than the sum of its parts.

project name project name project name

The loom was quite possibly the first ever machine. Impressions of woven fibre on clay fragments found at Dolní Věstonice in the Czech Republic date back to 25,000 BC, long before the dawn of civilisation. It is striking that two of the things that distinguish humans from other animals – wearing clothes and making art – are both associated with this invention. Perhaps it was through our interactions with this machine that we began to know ourselves more fully.

Looms grew more complex over time, but their basic function remained the same. In 1801, Joseph Marie Jacquard revolutionised the weaving industry when he invented the Jacquard head, a mechanism controlled by system of punched cards which enabled complex patterns to be woven automatically. Not long after, in 1837, these punched cards would inspire Charles Babbage to draw up plans for his Analytical Engine. Although never completed, this is now recognised as the first general-purpose programmable computer. Just as the loom threads back to our beginnings, so it spools forward into our digital future.

project name project name project name

Walter Gropius’ original manifesto for the Bauhaus, the German art school where Gunta Stölzl taught Anni Albers how to weave, was to create “a new guild of craftsmen without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist”. We now stand at an inflection point in human creativity, where computing power and blockchain technology have given us all the tools to create and disseminate art without a gatekeeper or middleman, and be rewarded fairly for our labour. In this new era of people's art, no arrogant barriers need exist. With the help of computers we can realise our creative potential and become not less human, but more. In so doing we will be answering the same urge as our ancestors. The loom stands in the cave. Now we must get to work.