Making of MONSTA FUNGUS

written by campyoutsider

Background

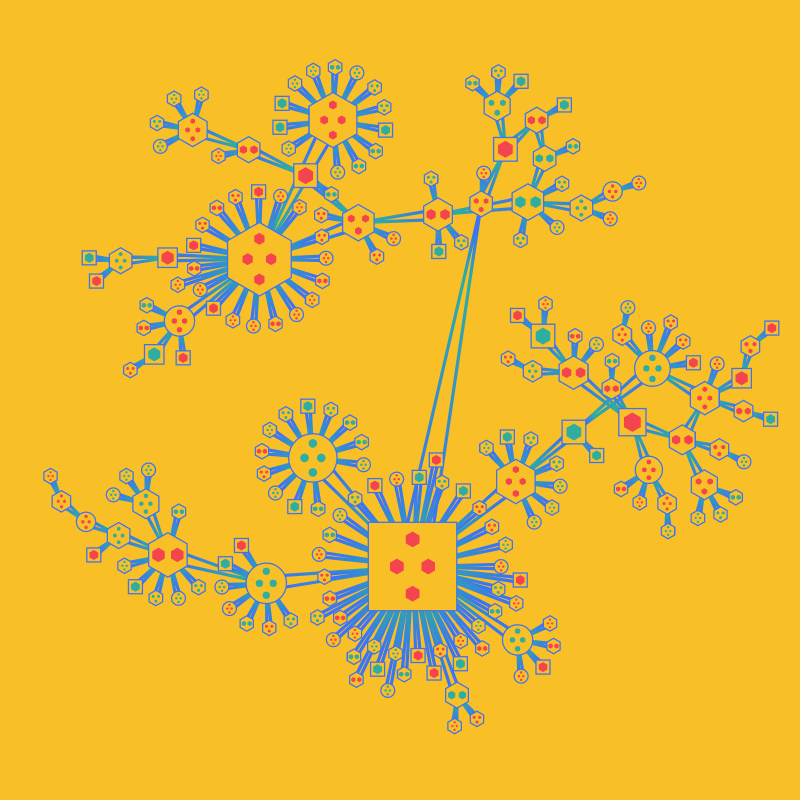

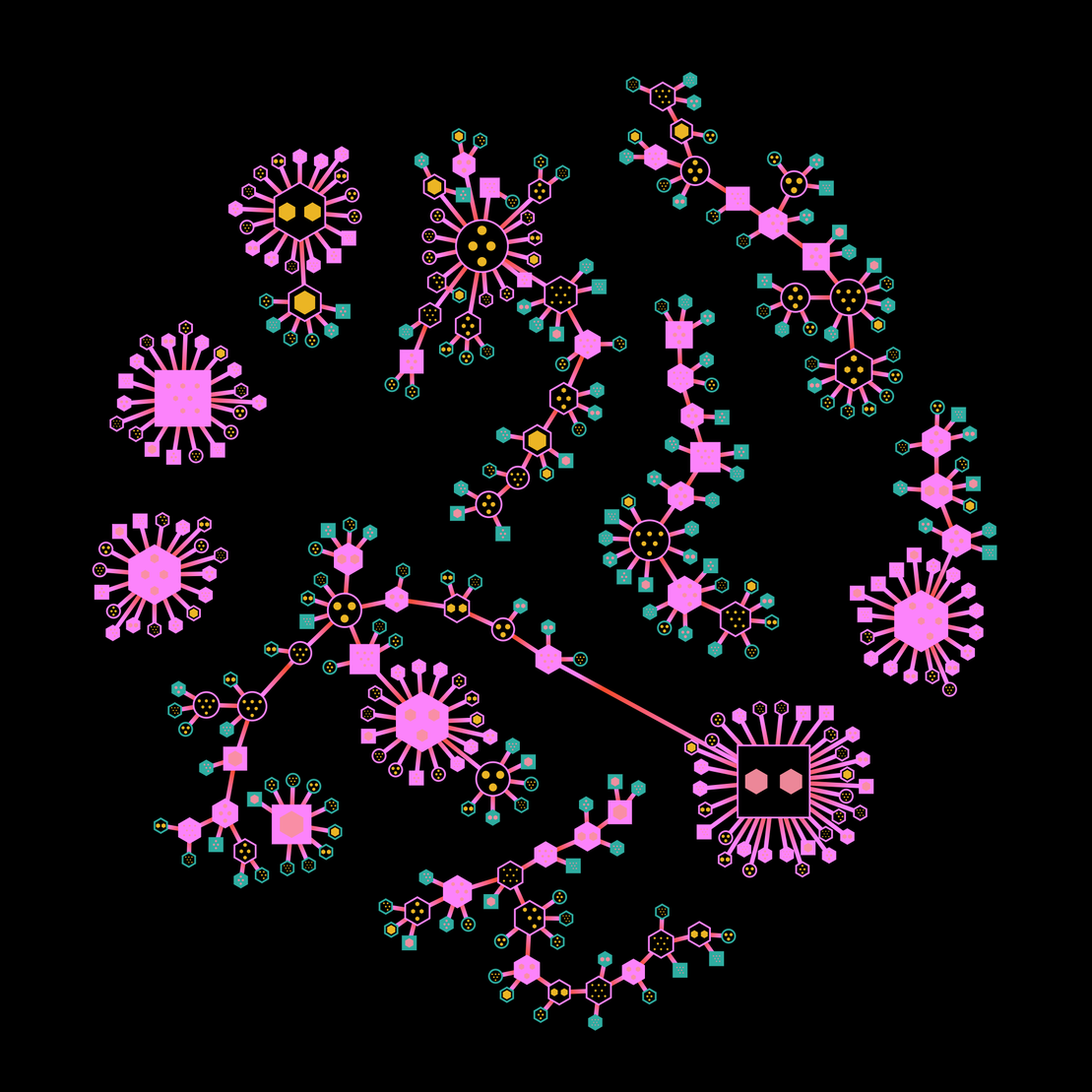

MONSTA FUNGUS was born out of my love for networks (or graphs as it is also referred to), which I stumbled upon through my interest in data visualizations. Networks represent connections, a desirable and important aspect in all our lives. They resemble an organic-looking structure which is very pleasing to the eye (in my opinion at least) and relate to nature, such as fungi, flora and fauna.

At its simplest form, each output is a network diagram created from a force-directed layout implemented by the Javascript library d3.js. In particular, the d3-force module was key to this entire project. I relied on this module to simulate physical forces on the nodes and edges of a network, to create a natural and aesthetically pleasing layout for all elements in an output.

Getting an aesthetically pleasing structure and positioning of nodes is important because it forms the skeleton of the output. I was also hoping to create sufficient variation in structures. Without any formal education in network science, I naively tackled this by creating my own simple network-creating algorithm. I knew that there needed to be a balance between clustering and path lengths. Highly-clustered networks look like ugly hairballs, while a network with too many long paths simply look like overgrown weeds. I did quite like the result of my algorithm, and was pleasantly surprised by certain outputs which I could not reverse engineer visually. I felt that ultimately all outputs do not necessarily have to represent a form that looks similar to commonly associated images of weeds, fauna or fungi. Early success in creating my own networks really did spur me on to continue playing with this project.

project name project name project name

Behind the Layout Algorithm

Here is how my own algorithm works

First, there is a single root node from which nodes spawn from. This means nodes keep getting attached to this root node, until a threshold count is reached. When this happens, the next node will find another target node. As each new node is introduced, each digit of the random seed derived from the on-chain transaction data is looped through and contributes to the selection of the target node ID. There is a new threshold count and the eligible range of target node IDs is adjusted. I term this a spawning cycle.

With the progression of each cycle or level, the target node IDs increase and should not deviate often from the range of values between the previous and current threshold. This creates very few linkages between leaf nodes of early hubs, which usually leads to a network that is more spread out with easily traceable connections. Nodes continue to link up with target nodes until the number of ‘levels’ is reached, or when all nodes have become attached.

for (let level = 1; level <= features['levels']; level++) {

let counter = 0

let currentThreshold = Math.round(scale(level) * elements)

let prevThreshold = Math.round(scale(level-1) * elements)

let prev2Threshold = Math.round(scale(level-2) * elements) < 0 ? 0 : Math.round(scale(level-2) * elements)

nodes.forEach((d,i) => {

if(i > prevThreshold && i <= currentThreshold){

if(counter === 15) counter = 1

let value = features['connectedness'] === '1' ? prev2Threshold + Math.round((currentThreshold - prevThreshold) * Math.min(seed[counter]/6, 1)) : Math.min(prevThreshold, prev2Threshold + seed[counter])

links.push({

start_id : d.id,

end_id: value

})

counter++

}

})

}

The Barabasi-Albert model

I also ventured into researching other random graph generation models, and was excited to learn about the Barabasi-Albert model, which is an algorithm for generating random scale-free networks using a preferential attachment mechanism. Preferential attachment means that the more connected a node is, the more likely it is to receive new links. This tends to create two or three major hubs around the canvas from which smaller hubs branch out from, which I feel gives a higher probability of having a nicer output.

Along the way, I enjoyed learning more about real-world networks. Here is a summary:

- Several natural and human-made systems, including the Internet, the World Wide Web, citation networks, and some social networks are thought to be approximately scale-free, meaning that they contain a small number of nodes with unusually high connections (hubs) as compared to the other nodes of the network.

- Networks that have a constant, random, and independent probability of 2 nodes being connected have a lesser tendency to cluster.

A deep dive into traits

All parameter values are assigned by using at least one of the 16 digits of this random seed. Here is a truncated version of the feature list:

const features = {

'elements': Math.max(200, Math.round(seed*500)),

'background color': blacklist ? "#000000" : bgcolors[seed[8]],

'element color': (bgcolors[seed[8]] === colors[seed[3]]) ? "#ffffff" : colors[seed[3]],

'link color': (bgcolors[seed[8]] === colors[seed[5]]) ? '#ffffff' : colors[seed[5]],

'shape type': getShapeType(seed[8], seed[9], seed[10]),

'distribution': ["linear", "sqrt"][seed[1] % 2 === 0 ? 0 : 1],

'anchor strength': Math.max(0.15, seed[10]/30),

'path style': seed[15] % 2 === 0 ? 'straight' : 'sloped'

}

Layout parameters

- Connectedness: The type of algorithm which the network is constructed from

- Levels: There is a constraint to the number of spawning cycles for nodes to prevent too long a path length. This input parameter is called ‘levels’ and ranges from 3 to 8.

- Distribution: Within each level, the percentage of total nodes that get attached is determined by either a linear or square root scale.

- Anchor to root: This determines whether there is a singular network or small separate networks. If there is no single root node, multiple small hubs result because any node has now the chance to become a hub based on the arrangement of digits in the random seed.

- Anchor strength: This determines how large a hub the root node becomes. This value has to be constrained, as I feel that a single node having too much influence (as how it also is in real life) is a rather ugly phenomenon. Anchor strength ranges from 15% to 30%, meaning that 15 to 30% of total nodes can become attached to the root node.

The total number of nodes to render is correlated to the random seed value. This ranges from 200 to 500 nodes. I wanted all networks to fit nicely on the screen with some padding around. To achieve this, the network has to be scaled down dynamically based on the number of nodes.

Palette

I have only one palette containing 10 colours, which is used to give colour to all elements (nodes and edges), including the background. There is an equal chance for a colour to be chosen as a background, except for black. Some colour combinations for elements with a background colour do not work well together, so I added a blacklist of these combinations, and replaced them with a black background.

I did not select colours based on a technical analysis of the components of each colour (hue, value and saturation) to prescribe whether colours in the palette work well together. I do acknowledge that this is an area of generative art that is worth studying and improving upon, and I hope to work on this for future projects.

Node style

There are a great number of possible styles a node can possess, but I had to narrow them down. There are 5 possible node shapes: circles, squares, hexagons, blobs, petals. These 6 shape combinations are assigned based on the random seed:

- only blobs

- only petals

- only circles

- only hexagons

- mixture of hexagons and circles

- mixture of circles, hexagons and squares

The node fill type determines whether all or some nodes are filled with colour or not. To add some decoration and uniqueness, all nodes contain nested nodes, the count of nested nodes within each node being determined by looping through each digit of the random seed and assigning that value as the number of nested nodes to render. There are two node colours and up to two nested node colours, which are assigned from the 10-colour palette.

Edge style

There are 2 possible edge types: straight or sloped. These paths can either have a gradient or solid colour fill. Colours also come from the same 10-colour palette For gradients, one of the colours is the same as the node to give a nice colour transition from edge to node. Sometimes, having too many colours and randomly styled elements works against the final output. I decided to control this by only allowing for either gradient paths or having nested nodes with two colours.

Musings

One of things I love about this year-long project of mine is my struggle to explain how the network forms from the lines of code I wrote. I only properly studied the algorithms when I was writing this piece. Sounds strange and sloppy? Well, that is very much a trait of mine. Another struggle is my obsession in adjusting small values to the input parameters, which did not help much with the bigger picture. I had a goal to release this project on fxhash, and pragmatically I knew a time has to come where I will have to stop agonizing over the code and embrace its outcome. MONSTA FUNGUS was published on fxhash on 21 August 2022 and I really do look forward to seeing more of them being revealed.

Want to see more? I have created a gallery of hundreds of MONSTA FUNGUS, showcasing the possible traits and structures of outputs. The web application comes with zoom, sort and filter features to help you observe each output better. You may also vote for your favourite outputs!