Lessons Learned from Implementing "Wave Function Collapse"

written by abetusk

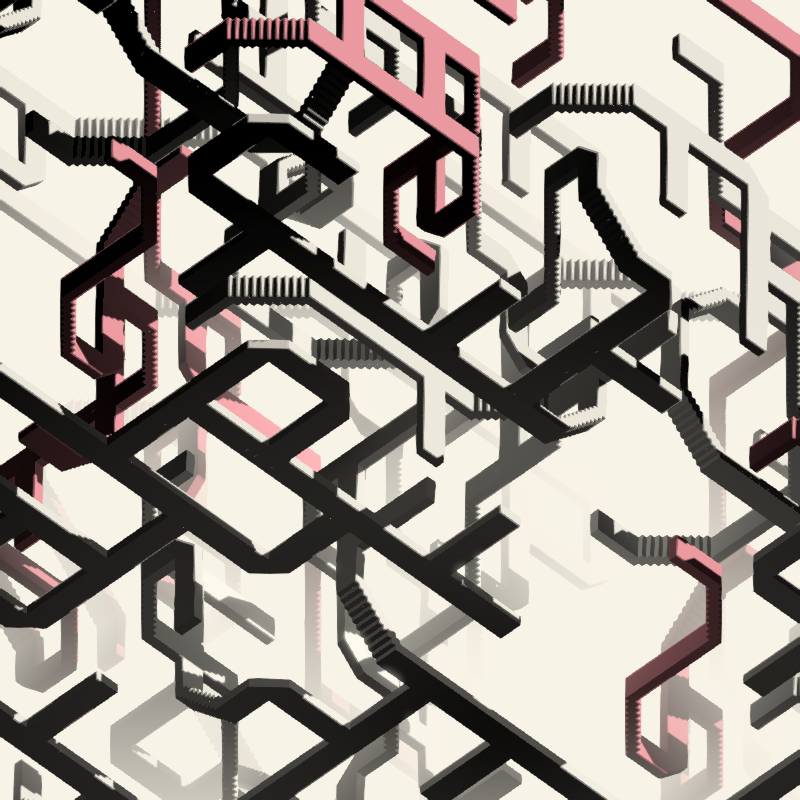

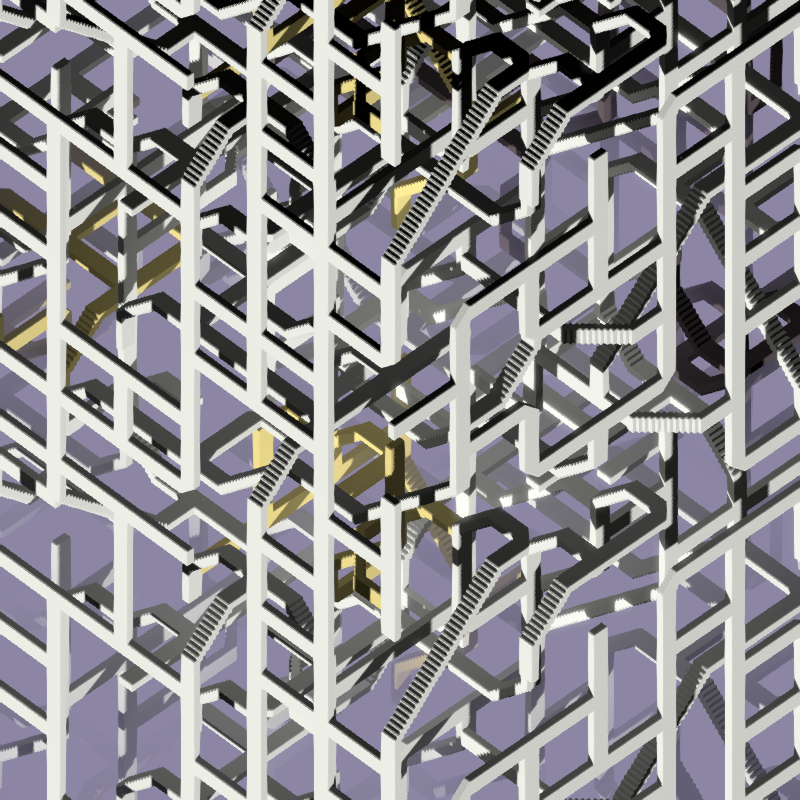

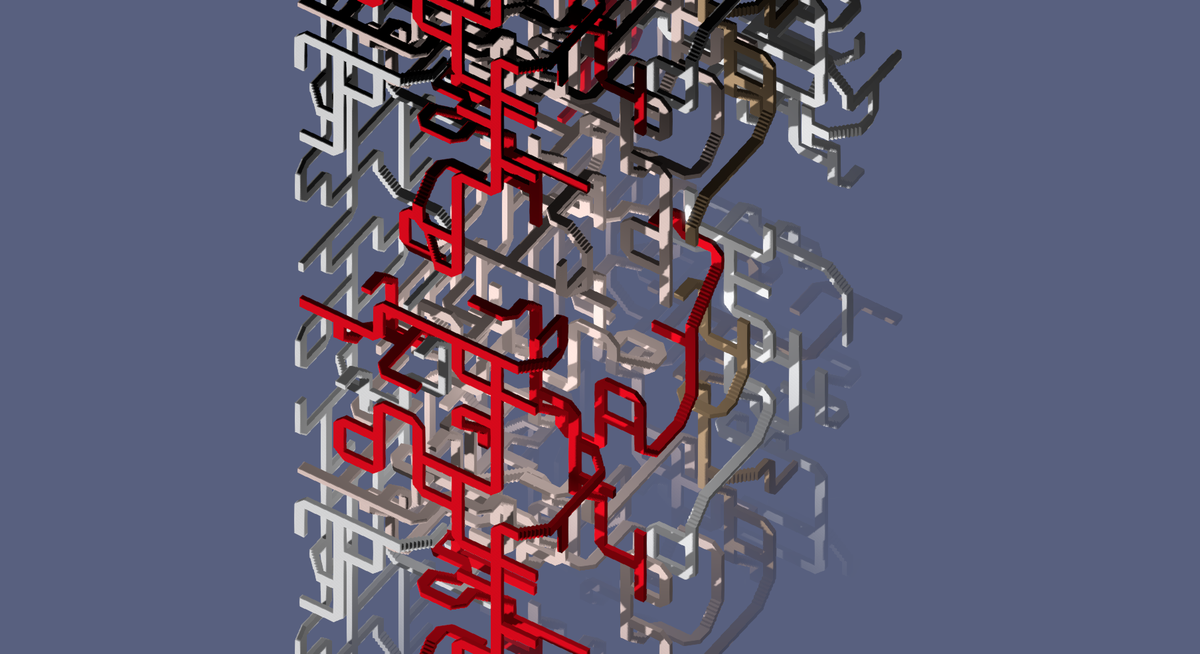

In the project "Like Go Up", a version of [mxgmn]'s "Wave Function Collapse" (WFC) algorithm was implemented to create 3D winding stair and platform like structures.

project name project name project name

This article is a description of some lessons learned from implementing a "Wave Function Collapse" (WFC) like algorithm. The aim is to provide a review of how the algorithm works and what some pitfalls were.

This article will go more in depth but as an overview, here are the succinct lessons learned:

- "Wave Function Collapse" works best with "simple" neighboring tiles and interactions. Anything beyond this assumption leads to an over complicated implementation.

- Tilesets need to be conditioned to have enough degrees of freedom. An overly constrained tileset will lead to failures in finding viable solutions.

- Optimizations that update only required elements, though straight forward and obvious, are necessary for appropriate execution speed

Overview

"Wave Function Collapse" (WFC) is a generative art tool by [mxgmn]. From the project site, "Wave Function Collapse" (WFC) is a:

Bitmap & tilemap generation from a single example with the help of ideas from quantum mechanics

Note that the reference to quantum mechanics is an homage, as [mxgmn] writes:

... it doesn't do the actual quantum mechanics, but it was inspired by QM

The implementation that will be discussed in this article is more of a "Wave Function Collapse" (WFC) inspired algorithm as it doesn't take any input image or scene. Instead, it uses a constructed 3D tileset to create 3D structures. The algorithm propagates constraints after choosing candidate tile positions to collapse via entropy minimization.

Briefly, this means for any state of the system, entries are removed if their presence would create a contradiction. Once all contradictions are removed, a candidate tile is chosen based on how "constrained" it is.

The forced removal of tiles is called the "constraint propagation" phase. The choice of a constrained tile to make progress is called the "collapse via entropy minimization".

Each of these steps and terms will be discussed later in the article.

Tilemap Setup

The library of 3D tiles consists, conceptually, of 7 different types of tiles (blank tile not shown):

From the "base" tiles, the triangle display geometry is calculated and a set of "endpoints" is created as an indication of how it can be attached to other tiles in the library.

Each tile that can connect to another has a grouping of 4 points on each edge that it can connect out of. These points are flush in the plane they sit on at the edge of a zero centered 1 unit width cube.

A complete "raw" library of endpoint rotations is constructed by rotating each base tile by 90 degree increments in each of the major axies, X, Y and Z.

By comparing the endpoints with either a rotated version of itself or with other rotated tiles, identical tiles can be identified and neighboring tiles can be identified.

From the duplicated list of tiles, a representative is chosen to represent different rotated versions.

For example, the "cross", if it lies flat in the XY plane, is identical to a "cross" that is rotated by 90 degrees around the Z axis. In this case, the tile +000 is kept and used as the representative as +001, +002 and +003 are all identical to it, where the + is the single character code for the tile and the three digits that follow represent the rotations in each of the three major axies by how many 90 degree increments it's rotated.

For each representative tile, a map of admissible neighbors is created that stores information about what tiles can be placed next to each other and whether they are connected or not. The only neighbor positions allowed are in increments of +/-1 in each of the major axies (X, Y, Z), excluding diagonals.

Tiles that cannot be next to each other are not in the admissible map. Tiles that are in the admissible map also have an indication of whether they are connected or disconnected.

For example, a road tile has connection points for other viable tiles in the +/-1 Y directions ([0,1,0],[0,-1,0]) in addition to allowing other tiles to be adjacent in the +/-1 X directions, so long as they don't have an incoming connection to it. In the above, the road tile can connect to a suitably oriented stair tile or is allowed to be next to a suitably oriented road tile that is parallel to it.

What is not admissible is if a road tile, say, were rotated 90 degrees in the Y axis and then tried to connect to the stair tile as before.

After the representative tiles are chose, the display geometry is created by rotating the triangle geometry for the canonical tile.

The endpoint representation and programmatic rotation allows for a semi-automated creation of the tileset. Additional tiles can be added by only adding the canonical tile geometry and endpoints, without the need to add the profusion of pairwise interactions that would result.

Note that the blank tile (.) is explicitly included in the admissible map. This means it is an error if any grid cell has all entries removed as the "empty" cell is explicitly represented by a tile.

Wave Function Collapse Algorithm

Once the tilemap has been constructed, we the wave function collapse algorithm can be run in earnest.

A cell grid is created that has each tile possibility at every cell position. The "wave function collapse" (WFC) algorithm proceeds to remove tile possibilities at any cell grid position it can until it runs out of choices.

When the WFC algorithm can't make any more progress propagating forced implications, it chooses a random cell, based on an entropy measure, and chooses ("collapses") a single tile for that cell.

After the tile is chosen for a cell, the cell and it's neighbors are marked for further processing. Flagging the processed cell and its neighbors is an optimization to focus on only cells that have the potential to change instead of wasting effort considering cells that are known to not need updating.

Here is the pseudo-code to the algorithm:

function WaveFunctionCollapse(grid) {

initialCull(grid);

propagateGridAll(grid);

while (true) {

clearTileFlags(grid);

r = collapseSingleTile(grid);

accessedGridPositions = {};

flagGridNeighbors(grid, accessedGridPositions, r.collapsedPosition);

r = propagateGrid(grid, accessedGridPositions);

if (r.state == "finished") { return; }

}

}

The bulk of the "wave function collapse" algorithm earmarks a single tile in a cell position to keep, then propagates the implications of choosing that tile by removing all other tiles that can never be chosen.

The initialCull is called to mark tiles that are invalid from the beginning, such as tiles on the boundary whose connection points fall out of bounds. The propagateGridAll is an unoptimized version of the propagateGrid function, described below, that processes all grid points without restricting to only 'marked' positions stored in accessedGridPositions.

Possible tiles are removed from the grid positions when they're culled from the collapseSingleTile and propagateGrid functions, using the accessedGridPositions structure to indicate which grid positions are to be processed.

The accessedGridPositions is the structure that allows the optimization of only updating cell positions that need it, rather than doing a full sweep over the whole grid.

The psuedo-code for collapseSingleTile:

function collapseSingleTile(grid) {

let minEntropy = -1;

let minCell = null;

for (let gridCell in grid) {

// skip already processed cell positions

if (gridCell.length==1) { continue; }

for (let tile in gridCell) {

tileProbability = pdf(tile);

cellEntropy += tileProbability * Math.log(tileProbability);

}

if ((minEntropy < 0) ||

(cellEntropy < minEntropy)) {

minEntropy = cellEntropy;

minCell = gridCell;

}

}

let chosenTile = pdfRandomChoice(pdf, minCell);

minCell = [ chosenTile ];

return { "collapsedPosition": minCell };

}

Most of the complexity of the collapseSingleTile function comes with calculating the entropy for tiles that have different probabilities which are encapsulated in the pdf (probability distribution function). The pdfRandomChoice is meant to choose a tile in a given cell with the probability or weight for any given tile.

Finally, the propagateGrid function propagates tiles in cells that are flagged for review if they aren't admissible.

The test for each tile in each cell is:

- If it has a connection that goes out of bounds, it should be culled

- If it doesn't have a valid neighbor somewhere next to it, it should be culled

Where a "valid neighbor" means either a neighbor that exists next to the tile in question, be it connected or no. An "invalid" neighbor is one where a connection is present in one tile but not in the other. For example, a "road" tile (|) that feeds into an empty tile (.) is invalid as the road expects a connection point where none exists for the empty tile.

The psuedo-code for propagateGrid is as follows:

function propagateGrid(grid, accessedGridPositions) {

let culling = true;

let updatedAccessedGridPositions = accessedGridPositions;

while (culling) {

culling = false;

removeFlaggedTiles(grid);

accessedGridPositions = updatedAccessedGridPositions;

for (let anchorCell in accessedGridPositions) {

for (let anchorTile in anchorCell) {

let neighborCells = getNeighbors(grid, anchorCell);

for (neighborCell in neighborCells) {

if (outOfBounds(neighborCell)) {

if ( hasOutgoingConnection(anchorTile, neighborCell) ) {

culling = true;

anchorTile.valid = false;

flagGridNeighbors(grid, updatedAccessedGridPositions, anchorCell);

break;

}

continue;

}

if ( ! hasAtLeastOneAdmissibleNeighbor(anchorCell, neighborCell) ) {

culling = true;

anchorTile.valid = false;

flagGridNeighbors(grid, updatedAccessedGridPositions, anchorCell);

break;

}

}

if (culling) { break; }

}

if (culling) { break; }

}

}

if (collapsedState(grid)) { return { "state" : "finished" }; }

return {"state": "processing" };

}

Some notable points:

- Anytime a tile gets culled, the cell and all of it's valid neighbors need to be reprocessed

-

The

outOfBoundscheck can be altered to contain wrap around conditions if desired

The above pseudo-code is meant more for illustrative purposes. An implementation of the above code would need to check for errors to see if it fails to find a realization by removing all potential possibilities in a cell position, say.

Lessons Learned

In experimenting with implementing a "wave function collapse" inspired algorithm, I fell into many pitfalls when creating the tile library and resulting implementation.

Pitfall #1, Privileging the Empty Tile

Initially, I did not explicitly treat an "empty" tile (.) as a regular tile. This led to increased code complexity because of the empty tile's privileged status.

When scanning for admissible neighbors, I would have to skip some tiles if they were the empty tile or do special case branching to handle the empty tile.

Instead, adding the empty tile to the admissible map and allowing it to be checked just as any other tile would be meant the special cases to consider the empty tile disappeared.

Pitfall #2, Complicated Tile Connections

The "wave function collapse" (WFC) like algorithm is conceptually simpler when tile neighbor tests can be treated in a homogeneous way.

This means not having special case neighbor tests for some tiles and treating every tile as if it can test for valid tiles next to it by considering a simple neighborhood around the position in question. One of the simplest ways to do this is to consider six cell positions in each [+1,-1] direction along the major axies.

Without this simplifying assumption, the code to find out which tiles are admissible neighbors to each other, which tiles should be culled, which tiles have no connections out of it or into it, or any of the myriad of other tests, quickly become overly complex.

Pitfall #3, Overly Constrained Tilemap

The initial tileset used didn't have a "dead-end" tile (p) and for many of the test runs, this resulted in failing to find a realization.

For small grid sizes, the realization would sometimes succeed, but as the grid sizes increased, the chances of finding a valid realization quickly diminished.

The issue, I suspect, is that without the "dead-end" (p) tile to allow for a chain of choices to easily be valid, a partial realization could easily get into a state where local consistency was achieved but a global or further reaching contradiction was either present or highly probable.

An enlightening example is in a 4x4x1 grid. Intuitively, only tiles "in plane" are the most likely. That is, tiles that are flat in the XY plane should be the most likely to be chosen for most realizations.

If a "stair" (^) tile is ever chosen, this drastically restricts the potential tiles available for any valid realization. Now, not only do the tiles chosen need to be either "road" (|) tiles or other stair tiles (^) in the XZ or YZ directions, it also needs to loop back in on itself.

The algorithm will start choosing other tiles that are locally consistent. Each choice that isn't considerate of the initial "stair" tile will further reduce the chance of choosing an appropriately oriented tile to connect.

One fix is to add tiles that allow more freedom of choice for any particular cell. In this case, adding the "dead end" (p) tile allows WFC to "patch up" a section that might have otherwise resulted in a contradiction.

An interesting question is what a good test is, even if it's a heuristic, to determine when tiles are overly constrained. It would also be interesting to determine at what threshold of size or grid structure any particular tileset starts to have issues converging in on a valid realization.

Pitfall #4, Not Optimizing

Folklore wisdom is "get it working, then get it to working fast", also known as "premature optimization is the root of all evil". Unfortunately, even moderately sized grids become unwieldy without optimization, so optimization is necessary very quickly.

Just from the initial setup of the problem, each cell needs to be visited at least once because it needs to be collapsed into a definite state. This gives already an $O(n)$ run-time, where $n$ is the number of cells of the grid. If the whole grid needs to be examined every update, this gives an $O(n^2)$ which grows quickly, especially when uniformly increasing each dimension of the grid.

Though it's difficult to say what the estimated run time is for the optimized version without some intricate knowledge of tile interactions, either for this setup or others, one can imagine a constant update time after each cell position is collapsed because only cells that have been altered are being considered, recovering an approximate $O(n)$ runtime.

Conclusion

project name project name project name

[mxgmn]'s "Wave Function Collapse" (WFC) algorithm is both an accessible framework to more theoretical ideas of constraint satisfaction problems but also conceptually simple and powerful that allows rich outputs from minimal effort.

The main drawbacks of it's inability to overcome local consistency, at the sacrifice of further reaching cohesion, are issues that grieve many similar classes of problems and algorithms in this space. Constraint satisfaction, as a general problem, is $\text{NP-Complete}$ so we have no hope of ever finding efficient algorithms. It would be interesting to pursue other heuristics to see if they can't keep the same ease and versatility in their use while providing more powerful tools.

References

mxgmn (2022) WaveFunctionCollapse [Source code] github.com/mxgmn/WaveFunctionCollapse

kchapelier (2022) wavefunctioncollapse [Source code] github.com/kchapelier/wavefunctioncollapse

Wikipedia (2022, September) Constraint Satisfaction Problem. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constraint_satisfaction_problem

Wikipedia (2022, September) NP-Completeness. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NP-completeness

License

All text, code, images and other digital artifacts in this article, unless expressly indicated otherwise, is licensed under a CC0 license.