Iteration is Usually Recursive — Introduction: Finding answers in pre-computational art

written by charlie

The following discussions are not an attempt at deciding what name best suits the generative art genre(s), but rather deciphering the connections between artists in an iterative dialogue as opposed to a gatekeeping polemic, and providing some much-needed context and history to the discourse. The naming can be left for practitioners and art historians to decide what to be called. Those who’ve been practitioners for longer than I, and those who are part of the new guard, have immense value in their views which I believe cannot be discarded wholesale based on a core disagreement of what is and what isn’t the correct word to call this art form. I think that knowingly or unknowingly, each practitioner plays a vital role in the progression of art as a dialect, a call and response of circumstance, itself a generative practice.

The rise of digital art and technology has led to a blurring of the lines between traditional art forms and those created using algorithms — for the first time in history, generative art is being sold on the international stage with the same strike of the hammer as legendary familiars from the traditional art market. For example, in 2018, the AI artwork Edmond de Belamy, by French art collective Obvious, sold at a Christie’s auction alongside Picasso, Lichtenstein, Warhol, and other household names for over $450,000.

In 2019, Mario Klingeman’s Memories of Passersby I was auctioned alongside Albert Albers, Damien Hirst, and Antony Gormley at a Sotheby’s auction. In a similar vein, Cure3, a charity exhibition for the Cure Parkinson’s charitable foundation, added seven generative artists to what has always been a very non-digital roster, including them amongst internationally recognised traditional artists such as Tracy Emin and Sir Frank Bowling.

As a result of this blurring, the question of what constitutes generative art has become a point of contention, not just within practitioner communities but at a much larger scale. Does generative, procedural, computational, algorithmic, or emergent art capture the work more accurately? These may seem the same to the layperson — from the inception of digital computer art, initially associated with a George Nees exhibit called ‘computer-grafik,’ these phrases have been employed synonymously. Others will point to these being entirely different methodologies and practices worthy of their own categorisation.

Through looking at historical accounts of the art form’s progenitors, such as Vera Molnár, John Whitney, and A. Michael Noll, and the methodologies of what is considered generative art in our current status quo, we can begin to build a robust foundational classification for specifically computer generative art. However, art forms predating computers can conceptually be considered generative art too, and must not be discounted as part of this dialogue. Introducing mathematical and geometrical rules into the production of art is as old as art is — even in the fields of music and architecture.

Additionally, embracing entropy as part of any creative endeavour is part and parcel of experimental practice. These analog practices, given thousands of years to develop by hundreds of thousands of practitioners, still strongly inform the digital practices of even the newest artists as they enter their work into the record — and, in our case, a public ledger.

Art's entropic function should not include all art in the same framework as generative art since defining all art as generative would be highly counterintuitive to the core of our discussions. To push the conceptual bounds perhaps into absurdity, one can experience nature as the most common example of generative art in the broadest sense.

Since the dawn of time, we’ve found profound beauty in our flora, clouds, stars, and everything in between, all created by perhaps the greatest entropic generator of all. Though too grand to be objectively classified, nature is so profound that it isn’t unusual that the simulation of its beauty is such a common theme for generative practitioners.

project name project name project name

Definitions that are often referred to tend to be predicated on an exclusive paradigm specific to digital programming, and whilst it is generally at least agreed upon, consider the work of conceptual artist Sol LeWitt; within a similar conceptual paradigm, LeWitt utilises the processing of natural language by the observer, forcing them to act as an artist,— written instructions to use a human as entropic art generator, no two imagined (or performed) results the same —, which expands the conceptual bounds of generative art into the analog, or even biological.

Based on my exposure to the digital generative art community over the last 10+ years and as an active practitioner in a professional capacity for the previous seven, there’s not been much agreement between thought leaders as a strict definition of what, within the medium, does and doesn’t constitute generative art.

When describing generative art, specifically in context to newcomers to fxhash (and the general paradigm of generative art), I tend to lean towards ‘generative art’ as an umbrella for all work that is supported on the platform — essentially work which utilities fxrand() correctly to produce unique editions upon purchase. We have decided, to facilitate some degree of ease when describing to newcomers, to settle our current definition of what broadly constitutes generative art as “a quasi-autonomous mathematical program with a specific set of algorithmic and aesthetic rules which uses entropy to intervene to create the final, unique, result.” In short, the artist makes the rules and gives away partial autonomy for randomness plays within their bounds. Though this statement was decided out of ease of conversation and introduction, and not as a declarative definition, there’s an objective boundary for what is, in the case of fxhash, generative art.

Since all modern generative art (using the previous definition) broadly follows similar mechanics, it means that the infinitely evolving proto-cellular organic simulations, static painterly abstract impressionism, and highly speculative monkey profile-picture (PFP) projects fall into the same fractal taxonomy. This banding together of multiple facets of programmatic graphic outputs has created heated debate to ascribe an objective value to one name over the other based on the work's subjective cultural, economic, and artistic merit.

project name project name project name

The constant renaming of generative art tends to involve going back to one of a few initial definitions, often depending on where one’s first exposure was to it, and tacitly redefining it based on the decided algorithmic and aesthetic trappings. Attempts have been made to claim one definition over another act as an argument of authority, rather than one by dialectic process. The definition of generative art has changed as new emergent art forms embrace the taxonomy, then that new definition is used to redefine the term itself. In practice, this is a recursive process.

Recursion is a logical function where the function calls itself, only ending when certain conditions are met. Otherwise, theoretically, it will continue to call itself until the end of time. We must draw a line in the sand to avoid being stuck in this loop forever. This constant changing of definitions by the new-garde puts into question the purpose of even using ‘generative art’ as the definition for this new boom in algorithmically made artworks.

Suppose generative art is a descriptor of a specific subset of primarily digital art. Within that, there are yet unnamed sub-genres (though they’re often identified by common programatic themes such as fractals, flow fields, recursive-subdivison, L-systems, and more recently AI), including ones that aren’t primarily digital (such as the plotter-twitter community). Then, one could argue that more effort should be put into identifying a correct taxonomy for the sub-genres rather than arguing about the potentially outdated head of the taxilogical hierarchy.

project name project name project name

If generative art descriptions can also encapsulate mediums which are analogue, it brings into question the legitimacy of the primarily digital arguments. Perhaps the name can be put to rest for more declarative identifiers — inclusive of historic artists and art, whilst not confusing somewhat opposed modes of thought regarding the analogue/digital conceptual paradigms. I believe the answer to this lies in the long lineage of art which follows rules — and those who have dreamed to break them from the inside.

By looking at the boundaries where analogue procedural art morphed into its digital counterparts, and identifying the historic definitions of this art and its movements, perhaps we can find a breakpoint for this ongoing debate — and if not, at least we can observe the process as a function of itself.

“In the computer, man has created not just an inanimate tool but an intellectual and active creative partner that, when fully exploited, could be used to produce wholly new art forms and possibly new aesthetic experiences.” —

A. Michael Noll

As the genre develops, artists experiment with novel forms of production of outputs including using generative process not as the end goal, but as a collaborative partner in digital and physical works, this can most easily be identified as the recent boom in AI assisted art. The prompt-writer conjures their painterly spell by way of a pandoras box filled brimming with latent space, and before them emerges the garbled regurgitation of a million mood-boards. The artist rarely knows exactly what they will get, but given enough re-prompting and redefining, from entropy comes order.

This collaborative theme is common across all generative disciplines, and even more so now as as artists are traversing from the digital realm into the physical. These infinite systems rely on a degree of curation from start to finish. As the generative system is sculpted endlessly to produce desired outputs, the artist must act also as curator of the parametric space in which the entropy operates. Additionally, the works often undergo a degree of manual curation of the outputs wherein the artist sifts through thousands of iterations to find the ones which most accurately represent the underlying system when prepping their works for exhibit.

To me, at the core of generative art, is the desire to seek beauty in complex systems, aesthetically or programmatically — and being able to traverse the poetic structures, sculpted from functional rhyming, requires an intersectional knowledge of technical and aesthetic systems. Generative art can be considered an aesthetic visage, symbolic of its underlying system. Beautiful code and and beautiful art is subjective - beautiful code does not always equate to beautiful art, and vice versa. Providing that there’s a foundational framework for what beauty is found therein, to most, knowing how it's crafted is irrelevant.

As the epoch of digital practitioners swings further to its apogee, and beings to shoot away from any recognisable orbit, the trajectory for generative art as a mainstay on the international stage is already set.

Artists can now wield complex machines capable of creating infinite beauty. The technological horizon has collapsed to a single screen you can fit in your pocket, and with it, so has the ability to experience this beauty from anywhere in the world.

“This may sound paradoxical, but the machine, which is thought to be cold and inhuman, can help to realise what is most subjective, unattainable, and profound in a human being” —

Vera Molnár

In the next part, we will compare the boom of the new wave of generative practitioners as a result of a very specific set of cultural and economic situations ,— specifically looking at projects like Bored Ape Yacht Club (Yuga Labs, April 23, 2021) and Fidenza (Tyler Hobbs, 11 June 2021) among others —, and compare the formation of this modern (and currently unnamed) movement to similar socioeconomic matrixes which paved way for the formation of niche, and highly influential, art movements.

This is the first in a series of essays, some long, some short, on generative art, theory and the practitioners of the medium. They will be released as and when they’re ready (ideally monthly/bi-monthly) with companion generative projects inspired by foundational generative art principles, works and styles, discussed within the writing.

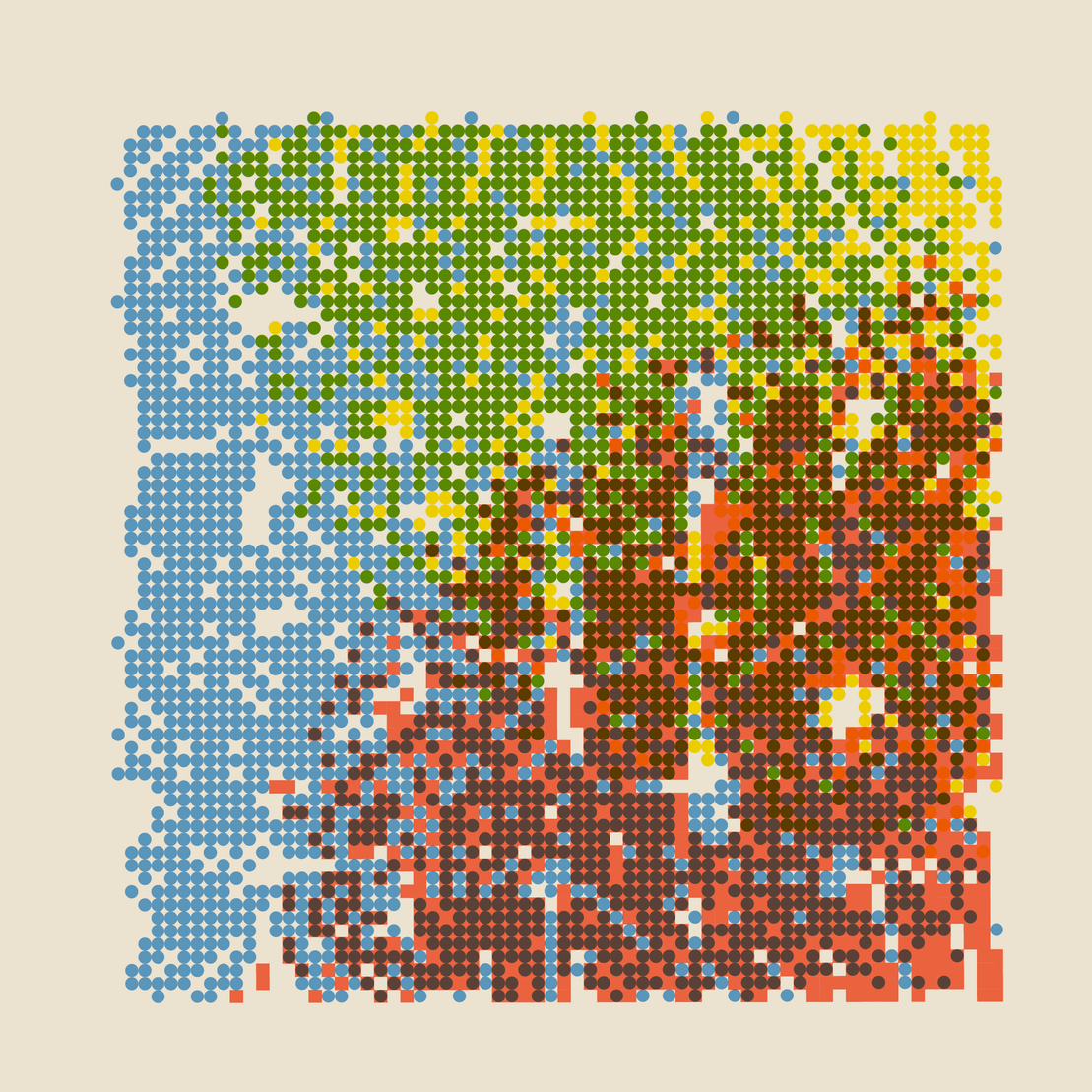

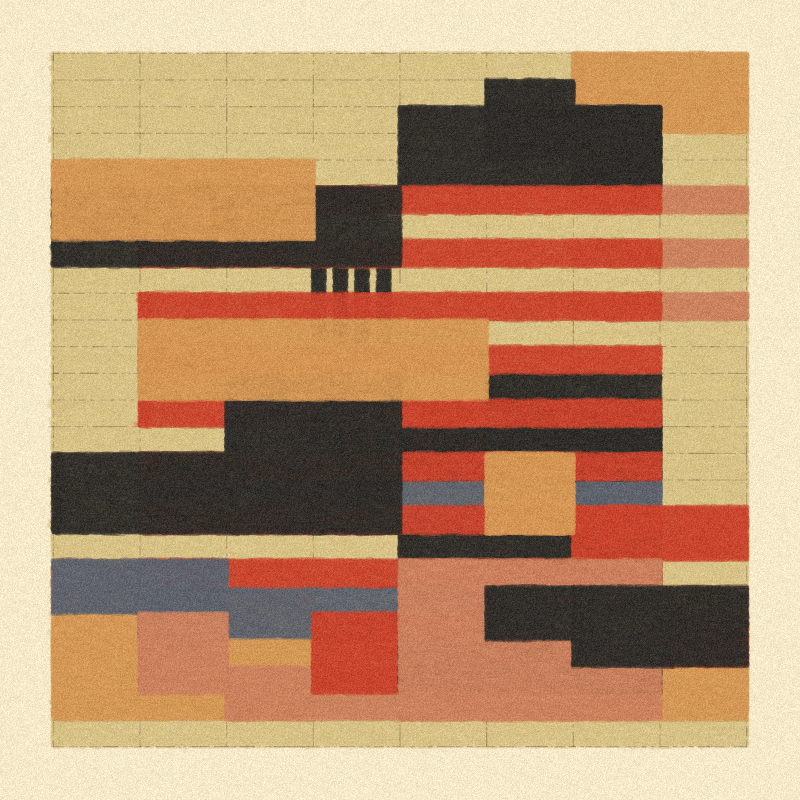

The companion piece released with this introduction started as an experiment with recreating George Nees’ Schotter (1968)— a classic piece of generative art history — as vanilla js SVG graphics. From there, I specifically developed it with non-plotter printing in mind, and more specific still, Riso Printing (think a scanner with a digital screen-printer MacGyver’d on). The palettes are taken from hex-estimated Risograph colour gamuts, with three layers being multiplied together to replicate, to some degree, the blending of the semi-transparent Risographic inks. Within this study, there’s a few different things going on, the initial setup is rectangles which cascade down the canvas, inheriting more extreme rotation as they get closer to the bottom (a la Schotter). The second is a subdivision of the shapes with filled circled, outlined circles and squares — since in this study the base shapes are rectangles and not squares, distribution of the ‘dithering’ can be larger than a single ‘pixel’ size — when these multiple layers overlap, the shapes produce a halftone-moire effect, forms and structures appear from the noise as the underlying patterns intersect.

project name project name project name

Thanks to Cosimo, Who?, Andreas Rau, Louis & Liam Egan for guidance, feedback, and listening to me ramble as I muddled my way though this introduction.

You can find me on twitter @ 0x0907