GTX unfolded

written by Jimi Wen

project name project name project name

Appendix I: A general relativity of calligraphy Preface

This preface is a first guide towards understanding the collaboration GAN and Glitch Calligraphy between Thomas Noya and I, GAN TING XU 幹亭序.

A 21st century preface to calligraphy.

What is calligraphy? Is it the writing of words?

There is architecture in calligraphy, but not where form follows function, rather form follows medium and the medium of medium. The function of calligraphy is on multiple levels: communication, expression, intention and intuition follow form. Firstly let’s look at some basics of Chinese and how it relates to calligraphy that is different to other arts.

Calligraphy of Language

All Chinese characters are logograms, but several different types can be identified, based on the manner in which they are formed or derived. There are a handful which derive from pictographs (象形; xiàngxíng) and a number which are ideographic (指事; zhǐshì) in origin, including compound ideographs (會意; huìyì), but the vast majority originated as phono-semantic compounds (形聲; xíngshēng). The other categories in the traditional system of classification are rebus or phonetic loan characters (假借; jiǎjiè) and “derivative cognates” (轉注; zhuǎn zhù). [1]

Pictographs: Many origins of Chinese characters are pictographs, that is meaning is figuratively write as characters. Here there is clear mapping of idea to a figurative symbol.

Ideographs and compound ideographs: Ideograms (指事; zhǐ shì; ‘indication’) express an abstract idea through an iconic form, including iconic modification of pictographic characters.

本; běn; ‘root’ — a tree (木; mù) with the base indicated by an extra stroke.

末; mò; ‘apex’ — the reverse of 本; běn, a tree with the top highlighted by an extra stroke.

Compound ideographs (會意; huì yì; ‘joined meaning’), also called associative compounds or logical aggregates, are compounds of two or more pictographic or ideographic characters to suggest the meaning of the word to be represented.

林; lín; ‘forest, grove’, composed of two trees.

森; sēn; ‘full of trees’, composed of three trees.

休; xiū; ‘shade, rest’, depicting a man by a tree.

Jiajie (假借; jiǎjiè; ‘borrowing; making use of, literally “false borrowing”’) are characters that are “borrowed” to write another morpheme which is pronounced the same or nearly the same.

Xingsheng (形聲; xíng shēng; ‘form and sound’ or 谐声; 諧聲; xié shēng; ‘sound agreement’)

These form over 90% of Chinese characters. They were created by combining two components:

a phonetic component on the rebus principle, that is, a character with approximately the correct pronunciation.

a semantic component, also called a determinative, one of a limited number of characters which supplied an element of meaning. In most cases this is also the radical under which a character is listed in a dictionary.

Appendix II: Calligraphy as medium and medium of mediums

The evolution of physical medium and their the corresponding calligraphy scripts written goes something like this from left to right:

There were various neolithic signs in China or aka Tao Wen 陶文- symbols of clear pictorial elements, but with no concluding evidence it was a language system. Also their lineage to oracle bone script Jia Gu Wen 甲骨文 —oracle bone script is also in question. Therefore there I start with the assumption that the oracle bone script is the start of Chinese calligraphy.

What follows and overlaps is the Chinese bronze inscription 金文. Where both started with similarities oracle bone script, bronze inscription diverged into engraved and cast bronze inscriptions. And the calligraphy body evolved within this medium is precursor of seal script and or the seal script 篆書. The medium between medium and mind is often carved or carved negative to cast on bronze.

The form follows the medium and the medium of the medium, i.e. the tool. The pen between mind and paper. For a simple distinction the calligraphy script for these hard medium are categorised as major zhuan shu 大篆. With the proliferation of bamboo and wood slips, a medium much easier to carve major zhuan shu evolve towards minor zhuan shu 小篆. Another significant factor in the usage of minor zhuan shu is the brush. Sharpe angle is enabled to flow with smoother curves.

Around the same time another calligraphy body li shu 隸書 arose out the necessity of efficient and natively a brush calligraphy body. So this parallel development in the Qin dynasty is political as well as technological and cultural. It is political, in that the political importance of unifying not only land territory but also culturally, i.e. language, therefore calligraphy body must be unified also. At the time minor Zhuan-Shu was reserved for more official documents and Li-Shu was more commonly used for everyday documents.

In the Han dynasty, Li-Shu became the main stream calligraphy script. A more compact calligraphy form to efficiently fit more language on medium, i.e. brush and paper. At the height of Li-Shu during the Han Dynasty, the other forms of calligraphy started to evolve from the official script of Li-Shu. Namely the earliest forms of cursive script Cao-Shu 草書, standard script Kai-Shu 楷書, and semi-cursive script Xing-Shu 行書.

In the evolution of Cao-Shu, two subscripts of the cursive script developed in succession, viz. Zhang-Cao 章草 the lesser abstracted cursive script from Li-Shu to the higher abstracted cursive script Jin-Cao 今草. Xing-Shu is the abstraction from standard script, balancing legibility and style.

Appendix III: Calligraphy as art

After the end of the Han Dynasty, Wei-Jin Northern Southern Dynasty, where aesthetic theories evides into function use of language. That includes the language written, language and literature itself and the physical forms of writing. Before this ongoing development of aesthetics of language becoming, language was only a tool, its utility is its function for communication. It is during this period that communication is more than direct intent of transmission of information or knowledge. Expression and impression are part of the communication, lyrical and in calligraphy. Wei-Jin Northern Southern Dynasty is the period of a new horizon of calligraphy as art. Not surprisingly literature became a genre of art too at the same period of time.

In the following period Sui-Tang Dynasty, there are both the consolidation and refinement of calligraphy rules of standard script Kai-Shu and the liberation of the wild cursive 狂草. This lead to a basic categorization of: Qing-Zhuan 秦篆, Han-Li漢隸, Tang-Kai 唐楷.

During the Song dynasty many great literati/calligraphers attempted to break away from the rules of Tang-Kai, in search of individualisation and liberalization, both a desire or the objective of the calligrapher. The ongoing war around the Song-Dynasty neighbouring countries often led to a kind of helplessness and melancholy. It is also a period of massive documentation of past remaining calligraphy. This has helped future generations to study calligraphy. Not many real calligraphy work past the Song dynasty has survived.

There was a revisiting of all main five scripts during the Yuan dynasty of Zhuang-Shu, Li-Shu, Kai-Shu, Xing-Shu, and Cao-Shu. As change of government so does the trend in calligraphy reflect. As minority rulers, the Mongols attempted to assimilate into Chinese culture as a ruling strategy.

When the Ming dynasty overtook the Yuan dynasty, and then restarted the imperial exam prefered standardised standard script without any individuality. This is by no accident, due to the humble background the Zhu Yuan Zhang (朱元璋). By mid Ming Dynasty calligraphers studied calligraphy in reverse order from more recent calligraphers to further into the past. In the mid Qing dynasty, calligraphers began to take interest in calligraphy further into the past, specifically Zhuan-Shu and Li-Shu. And to study the original sources the calligraphers looked at engraving in stones.

Appendix IV: Calligraphy as form, as semantics, as intuition.

It can be seen that the principles of “form follows function” is applied to calligraphy easily. But the form also respects the material, external or internal. That is calligraphy is both functioning as language and in language the forms have function. But calligraphy is not an abstract language in the sense of Chomsky of universality, calligraphy rather is particular.

That is every stroke is of universality, as to communicate amongst others, and of individuality, that there are infinite many parameters that make up a given calligraphy piece. Whether brush or engrave or casting, different mediums of bones, stone, paper etc. Like art there exists tension between universality and individuality. Pure universality is a standardized product with perfect quality control. For example your iPhone. Pure individuality is one’s ego, id, super ego etc. Art in general or in the case of calligraphy is exactly the individuality that is externalised form on paper with function for communication, expression, impression etc with universality. .

Asemic calligraphy is only calligraphy with universality of one person. Normally calligraphy of various script has an universality of more than one person.

In my humble opinion calligraphy cannot only be expression or impression, otherwise it is just painting with universality of Chinese characters individualised visually only. It is in no coincidence, the three most recognised Xing-Shu is all Wang Xi Zhi’s improvisation during the emperor celebration, or Yan Zhen Qin letters or diaries of Su Dong Po. It is in the intent in communication that there is ground for the language written. Secondary is the expression and impression of forms. Merely expression of the already expressed intent, at best abstract or figurative, is not unlike Pollack or Bacon, not calligraphy, they are panting. I am not quite sure what exactly is pure impression of calligraphy. Perhaps asemic calligraphy without intent is an impressionism of calligraphy.

Therefore it is impossible to separate not just the content of the communication in calligraphy, but also where, why, who , how of the intent is equally critical. Otherwise calligraphy is reduced to painting. It is after the intent then expression and impression is freed into form as they follow the function, intentionality. Definitely not function following the form. Which is essentially post-hoc conceptual art.

Of course there is intuition in writing some else’s classical poetry, but I would argue this triggers a type of passive intuition. Active intuition is innate in poetry or verses that the author expresses both in semantics and visually. There is a gap between fixed encoding of words making up sentences and the actual semantic ambiguities that exist. And from there is another gap between the semantics and the intention of expression. Calligraphy is the attempt to bridge these two gaps.

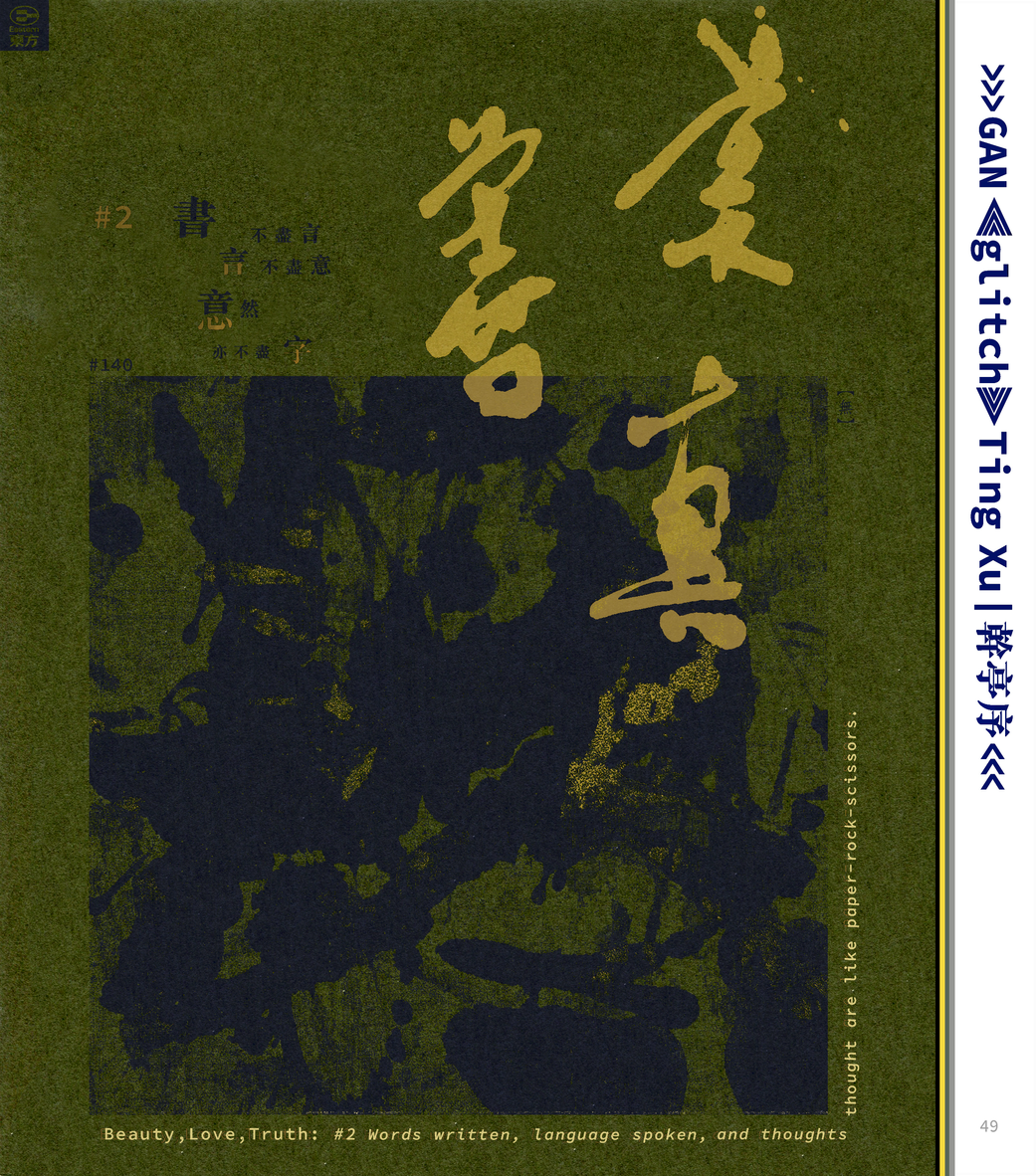

The first gap is bridged by different applications of each character onto the space. Writing someone else’s word is essentially bridging the first gap. The second gap is between complex intention to semantic and syntax. Which in combination first gap produces well know gaps in calligraphy from I-Ching:

書不盡言,言不盡意。

generally translates as: our calligraphy cannot complete our expression, and our expression cannot complete our intuition (intention).

Rather than taking this as a theorem, in calligraphy, or in writing, the theorem becomes a challenge, not to disprove contradiction, but to bridge the incompleteness. Although it is necessarily incomplete, the act of completing, towards sufficient completeness, is art.

Taking a more dualistic stance, I believe I-ching’s monist stance ignores the recursive loop that is obvious to me. That is

意(奕)不盡字(書)

closing the incompleteness loop, that all intention and intuition cannot complete all of the calligraphy. This is what I believe Xu-Bing attempts to suggest the incompleteness of our intuition. But nevertheless he implicitly left it to the intuition of the viewers.

Appendix V: Calligraphy into 21st century

What can be said is not all that can be written. What can be thought is not all that can be said. That said, what is written is not all that can be thought of. In GTX, 幹亭序 Thomas and I attempt at examining the incompleteness of calligraphy. This section is where human and GAN Calligraphy fits with respect to —GTX GAN TING XU 幹亭序.

In this section we first look at the limited samples of my calligraphy. Then we take a look at the GAN calligraphy trained by Thomas.

In Figure 1. we review along the x-axis the evolution of the main Chinese characters. On the y-axis, we have the various forms that evolved and stabilized over time, viz. Standard Script, Clerical Script, Semi-Cursive Script, Cursive Script, and Seal Script Major and Minor.

Appendix VI: The GAN training of my calligraphy

I might have only taken 2 calligraphy classes in elementary school. More than three quarters of my education was in English. When I first moved back to Taipei, I had trouble writing Chinese. It’s only when I studied classic Chinese literature that I began to take interest in Calligraphy. Typically “good” students of calligraphy copy the great masters stroke by stroke of the past, viz. lin mo 臨摹. Fuck that, the words speak for themselves, I just put them down on paper. I might have a quick look at different calligraphers. To me calligraphy is not about writing pretty, it is beautiful writing, the visual, the semantics and intuitive understanding of the subject.

It is also for this reason I do not copy poems or poetry of other poets. This is only a matter of ego. If you have nothing to say, you will have nothing to really write, sans some superficial aesthetics. On the other extreme if I write completely novel, the communication utility of calligraphy will tend towards zero. In finding a balance, I’ve decided to accept writing calligraphy if I own the majority, i.e. 51% of the poetry. That is I can match either the first line or the second line, with a change or sharing a word.

It can be seen that I do not write proper seal scripts. Yet my standard script is nearing semi cursive. And my clerical script came by a way of accident by writing with two hand two brushes. In the basic five calligraphy script, there is usually not much difference in the file size to words written. They were all efficient systems of writing. It is when we cross from shufa 書法 to shudo 書道, that expressionism takes over efficiency of communication. Though one could argue different dimensions of information are communicated implicitly.

There are only ways out of the traditional classical scripts, one is expressionism, the other is codification or deconstruction of codification. Many contemporary artists take the former with different techniques according to their aesthetics. For the latter, Xu Bing, deconstructed standard script and scrambled the formation of each character. For me the codification route is obviously not playing around with permutation of word components. But rather revert calligraphy at brush hair level from generative code. Early experiments of codification are on the upper right quadrant.

Appendix VII: GAN Calligraphy

I was really interested when Thomas approached me with using GAN and Glitch on calligraphy. This is exactly taking expressionism further than one could with brush, ink and paper. We have all that plus CPUs, GPUs, cameras, photoshops, p5js etc. The aim of the project is to explore limits of expressionism whilst within bounds of what I could still call the works of art calligraphy.

A total unexpected result we saw with the GAN training. The more iterations it trained as seen in Figure 3, we went backwards in time. This is not a scientific experiment, it is an art experiment. So sample sizes, diversity of my calligraphy are not controlled. It is as if without formal training of classical calligraphy, there are strong traces of the most intuitive calligraphy without becoming stylish in dominant cultured scripts. The more backward in time the more universal it is to humanity independent of cultural context. The raw intention to communicate and express.

Appendix VIII: General relativity of Calligraphy Abstract

言無言

言無言,

言,相之表述,

又言,語裡之象,

於象離相,見眾象非相,即見如來,

無相而象無言,非非相,非非象,非非言。

The limits of expression (言) is in our imagination (無象).

Expressions, imaginarily inconsistent (非相), are implicitly incomplete (無相無言) in scope. Within the scope, the limits of expression is in codification (言), finite translations (象) without infinite precision (非非相).

行有形

行有形,行作而形著,

而著,而行,而作;

有著,有行,有作。

行作之初,行隨作往來,

形著之始,形並著出入,

作中之著則行旺,

著中之作則形盈。

形由行,著形至作行,

至行,至著,至形;

由著,由形,由作。

著形之午,形由作降,

作行之子,行由著升。

作先行,後浮出作,

著先形,後沉入著。

作又著,行作以著形,

以行,以作,以形;

又行,又作,又形。

行生作以形收,又以行煮以話形,

著畫形以作聞,又以著行以聲作。

著遊作,

作佐行有形又著以作由,

著作形由行右左依著遊。

Acting is of forms.

Acting the act and forms form. (行作而形著)

The act on forms and forms in act. (作形[而著]行)

Forms form and the acting acts. (形著[而行]作)

Acting of the formed and an act forms. (著行[而作]形)

Act forms. (作[有著])

Form acts. (形[有行])

The formed is an act. (著[有作])

In acting the act, an act follows the acting.

Of formed forms, forms become form.

A sensation is an act in form.

Intuition is a formed act.

Forms from acting formed forms to acting in an act.

Forms act on acting forms. (形作「至行」著)

Acting in an act on formed forms. (作行「至著」形)

Acting forms unto forms act. (行著「至形」作)

Act from formed.(行「由著」)

Formed from forms.(著「由形」)

Forms from an act.(形「由作」)

Abstraction from acts to form.

Figuration from acting to form.

Performance is an act surfaced from acting.

Compositions formed are deposits of forms.

Act and then formed, acting the act is with form.

With acting. (形著「以行」作)

With act (著行「以作」形)

With form (行作「以形」著)

And then acting (著「又行」)

And then act (行又作」)

And then in form (作「又形」)

An act is the acting and ends in form. This act is then cooked with words on the menu.

The drawing, formed in forms with its sounds heard. This drawing then acts as forms spoken.

Formed trip.

Go on a trip with a dash of dripping foam torn into treats.

Formed crit combs from the track right, and what is left of the trip.

思無字

書者字之道法,言者文之相象,意者心之思念。

字,形法于心,尋思以達意,法無一法,法印假象。

字,行道于心,想念以意會,道不足道,道不似相。

心,著思于文,抽象以無言,思無一思,思存假法。

心,作念于文,共相以言外,念不足念,念不失道。

文,行象于字,依法以書畫,象無一象,妄象假念。

文,形相于字,知道以來信,相不足相,相不思過。

書不盡言,言不盡意,意然,亦不盡字。

道形字著,法行字作,相形文著,象行文作,形思著意,行思作念。

相一心,象無心。

法一文,道無文。

眾一念聚以一字,一眾思拘無所字。

念一字,思無字。

TLDR: Words written, language spoken, and thoughts thought are like paper-rock-scissors.

In long form with expanded footnotes with additional illustration between the three worlds of: 1) physical written words 2) platonic form of language 3) mental/conscious of thought.

The koan revolves around this model between the 3 worlds. Each transcend into another, and is transcended into by the other. In each local world model, there is a fig.1-like circularity. However a simple circle is more surface like, e.g. mobius-strip. e.g. fig.2i.

「書者字之道法」coming back to the first line and fig.2i 書:book, writing or letters.. 字:word (character) 道:way ~ “tao” “dao” 法:law, rule. Calligraphy in Chinese traditions has developed (dominantly) as 書法 and in Japanese as 書道.

The reason I make the analogy to the Möbius strip, is what ever divergences there are with 道 and 法, there is no inside outside, it's all on the same side. In a sense it's not even two sides of the same coin.

言者文之相象 言 = language (semantic+spoken) 文 = text (syntax+prose) 相 = image (negated reality in Buddhism as 無相) 象 = image (affirmative reality in Taoism as 大象(無形)) Language is imaged/imagined text.

意者心之思念 意:will, conscious, 立 曰 心~= today I speak 心:mind, literal heart 思:thoughts, reflections before reflecting, 田心, field project from mind 念:thoughts, remembrance of present, 今心, what’s on my mind today. Conscious is the thoughts of mind.

Skipping the main body of text. Jumping into the antithesis: 「書不盡言,言不盡意」- I-ching https://ctext.org/book-of-changes/xi-ci-shang/zh… ~= what’s is written cannot express all we want to say, what is said cannot mean all we really feel.

I posit the following: 「書不盡言,言不盡意,亦然,意不盡書,亦然,意不盡書。」 ~= what is felt, is not all there is to write/express. Or of all the expressions, it is felt by the many. That is closing the loop between fig.2i, fig.2ii, and fig2.iii.

「道形字著,法行字作,相形文著,象行文作,形思著意,行思作念。」 Appendix 1 refers to the mapping of the fig.1 model: Form 形 , formed 著, acting 行, act 作. to each of the three different world models in fig.2i, fig.2ii and fig.2iii.

Derivation results: 「相一心,象無心。法一文,道無文。」 By substitution (眾一)念聚(以)一字,(一眾)思(拘)無(所)字。 Many of one thoughts merge as one word. One of many thoughts is encapsulate by no one word. QED 念一字,思無字。 Thoughts lost for words.

心由幸

沾苦淡閒言,

甘問宮,幾步多;

路回足,自行走,近圓空。

似作達而意煮,辛油形即答心。

行形作著,書字道法,言文相象,心思意念。

Dipping in lightly bitter sauce of leisurely talk,

Sweetness asks of do, how many more steps?

The road replied to my foot, keep walking, until you reach a rounded emptiness.

Like an act until thoughts are cooked, chilli oil shapes the answer of my heart.

Acting and forming, act forms, or forms act. The rules and way of calligraphy, the language, texture, images and imagination, heart and thoughts, thinks and feels.